In this article, I want to do several things. First, I want to explain what capital goods are and how they enhance the productivity of labour. Secondly, I want to explain the principle of time preference and its role in the determination of market interest rates. And lastly, I want to explain how a general increase in savings shifts the focus of an economy's output from consumer goods to capital goods, thereby increasing the standard of living in society.

Capital Formation And Economic Growth

Economic goods are scarce physical objects that can satisfy human wants. Those that directly satisfy wants are called consumer goods, and those that only indirectly satisfy wants (because they contribute to the production of consumer goods) are called producer goods. The category of producer goods can be further divided into land, labour, and capital.

Land includes all the nature-given factors of production, including natural resources. And labour is the physical effort of the individual engaged in production. Capital goods are the non-nature-given factors of production. In other words, producer goods produced by human beings.

Capital goods are the key to greater productivity, both in terms of increased quantities of goods producible with machinery and equipment and in terms of goods producible only through the employment of capital goods.

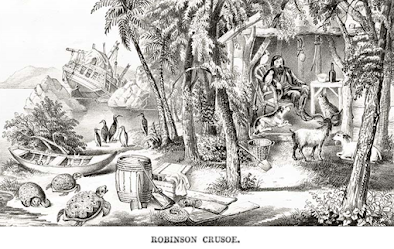

To explain how this works, imagine Robinson Crusoe shipwrecked and stranded on a desert island. He is cold, thirsty, and hungry. Unhappy with his situation, he takes an inventory of the goods at his disposal and decides to engage in production in order to improve his state of affairs.

He observes that the most easily obtainable consumer good on the island is fish. Let us assume that with the use of his hands alone, he can catch 5 fish per day, provided he works for 10 hours. let us further assume that eating five fish per day is sufficient to sustain his health.

As a result of his hand-to-mouth existence, Crusoe's standard of living is desperately low. Moreover, he knows that if he was to fall ill or injured, he could easily perish.

There is a solution. The solution to Crusoe's dire poverty, as it is to the poverty afflicting any society, is production. His productivity would be greatly augmented if he could acquire a capital good; namely, a fishing rod.

However, in order to produce a fishing rod, Crusoe must first engage in saving. As Mises noted, the only source of the generation of capital goods is saving. In other words, he must consume less than his income allows. Through the act of saving, he will acquire a stockpile of fish which will eventually enable him to divert his labour and natural resources to the production of a fishing rod.

Accordingly, Crusoe begins to save one fish each day. After he has accumulated an adequate stockpile of fish, he is able to begin work on his fishing rod. Before long, and thanks to Crusoe's act of saving and investment, he has a new capital good: a fishing rod.

When he tries out his new capital good, he discovers that his productivity is drastically higher with the fishing rod than without it. With the aid of a fishing rod, Crusoe can catch 2 fish per hour. Consequently, he can now produce 15 more fish per 10 hours of work than he could with only his bare hands. His greater labour productivity therefore increases his income and welfare.

The Robinson Crusoe analogy illustrates how saving and investment is a prerequisite of capital formation, and therefore the key to increasing everyone's incomes. This so-called "Crusoe economics" has been frequently derided by critics. However, the criticisms are unfounded because the general principles derived from a single individual acting under scarcity also apply to billions of individuals interacting in a modern society under the division of labour.

The Determination of Interest

Interest is essentially a product of the universal fact of time preference. The principle of time preference means that individuals prefer present goods to future goods. The potency of time preference varies from person to person, but it is a universal principle that applies to all human beings.

Opponents of the market economy may attempt to deride interest as "capitalistic exploitation", but this assertion is unfounded and stems from an ignorance of economics. Interest is a manifestation of the principle of time preference. All of us, including the socialists, possess time preference. Interest is therefore an ineluctable feature of human existence and cooperation. Like supply and demand, it can be suppressed but never abolished.

To see more clearly how time preference gives rise to interest, consider the following: is $100 today worth the same to you as $100 one year from now? Naturally, the answer is no. Except under special circumstances, no one would exchange $100 today for a secure promise to be repaid $100 in a year.

Of course, it is conceivable that under some circumstances we may be willing to make this exchange; for instance, if the exchange was a gift to a family member. However, this is emphatically not a refutation of the general principle of time preference.

For most people, they must be compensated in order to make this exchange. That compensation is called interest.

Interest can be therefore be characterised as the discount on future goods and likewise as the premium on present goods. One way to think about interest is that it represents an exchange rate between present goods and future goods, but instead of converting between different currencies, it converts between the same currencies in different time periods.

Savings and Investment

Interest is often expressed as a percentage of the principal (the initial loan); this is the interest rate. Sometimes interest is erroneously referred to as the price of money. More accurately, interest is the price of borrowing money.

We shall now consider the role interest plays in the process whereby an increase in the amount of saving by market participants results in greater capital formation and therefore greater economic growth.

Imagine that for whatever reason more and more people have decided to forego present consumption and engage in saving. This reduction in consumption spending would mean that high-end restaurants, for example, would see a fall in their sales, and they would therefore reduce their inventory, cut their workforce, and close some of their stores.

However, although consumption spending is initially much lower, investment spending is proportionally higher. The increase in the amount of savings would result in an increase in the amount of investment in the economy. This boon to investment can be direct (i.e., buying stocks and bonds) or indirect (i.e., putting money in a bank account).

The displaced labour and capital would eventually be redirected from industries that cater to immediate consumption and toward longer-range production. This shift in the pattern of production would be guided by interest rates.

Let us assume that the initial equilibrium interest rate in the loanable funds market was 7%. At an interest rate of 7%, lenders want to lend out the same quantity of funds that borrowers want to borrow; it is called the equilibrium interest rate because it equilibrates supply and demand.

As we saw, the increase in savings led to an increase in the amount of lending and investing in business. This increase in supply would eventually cause the interest rate to fall. The graph below depicts such a rightward shift in the market supply curve.

At this lower interest rate of 7%, longer, more time-consuming ventures are now profitable. The reason for this is that the discount that accountants must apply to evaluate profitability is now considerably less than it was under the old market interest rate of 9%.

Thus, the entire structure of production will become more future-oriented, and the growing stockpile of capital goods will increase labour productivity all round. After all, workers can be more physically productive when aided by increased numbers of machinery and tools. The greater output means greater economic growth, and the enhanced labour productivity means higher wages.

Conclusion

This lesson of economics is arguably one of the most important for any well-informed member of society to understand. As Friedrich Hayek said, before we can understand how things can go wrong in an economy, we must first understand how things can go right. Things go right when entrepreneurs employ resources to satisfy the more urgent preferences of consumers, and it is through the guidance offered by market prices and interest rates that they do precisely that. It is when the government intervenes and interferes with those prices that things go awry.

In a future article, I will explain how government interference with interest rates through credit expansion results in the boom-bust cycle. But for now, the important lesson to bear in mind is that the path to economic growth and prosperity lies in savings and investment.

Bibliography

Rothbard. 1962. Man, Economy, and State.

No comments:

Post a Comment